history

>We work in these places. We sew clothes.

>

Debbie Nathan on the collision of history, immigration, and language learning @ Mr. Beller’s Neighborhood.

In the spring of 1980 I was a cocky new teacher of English as a Second language, fresh from education grad school, with innovative pedagogy that I couldn’t wait to try out on students. My first job in New York was a gem: “Vocational ESL.” It was funded by the feds and I’d gone to the French Quarter in New Orleans for training. By night I’d visited blues clubs to see Professor Longhair. By day I’d studied how to teach foreigners words like “key punch card, “on-off switch” and “transmission.”

|

| Debbie Nathan on Amazon |

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )Back in Manhattan my new workplace was called Solidaridad Humana—Human Solidarity. It was a giant shipwreck of a public school on Suffolk and Rivington Streets, long abandoned and vandalized before being commandeered by militants and mural painters with barely enough funds to clean the graffiti. The temperature inside was ridiculous even in March: we had no heat from oil. But there was plenty of heat from enthusiasm. The students were all recent arrivals from the Dominican Republic. Their population in New York was still small then, and they were breathtakingly ambitious. I had the vague sense they worked in shady places for illegal alien wages, and I knew they wanted clean labor in bright offices and big auto repair shops run by Americans. I knew because those were the jobs whose vocabulary I was supposed to teach them. And these were the words we used. We never talked about how they made a living in the meantime.

>An intimate new friend in the house of books

>

|

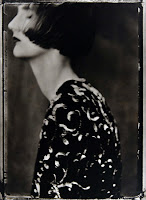

| Sarah Moon @ Lens Culture/ |

Keri Walsh remembers the influence of Adrienne Monnier on the life of literary Paris @ Brick.

Sylvia Beach said that she had three loves: Shakespeare and Company, James Joyce, and Adrienne Monnier. For mysterious reasons—perhaps because she wrote in French, perhaps because in the age of high modernism she preserved the habits and demeanour of the nineteenth century—Monnier was passed over for the international fame that went instead to the women she inspired: women such as Beach, Gisèle Freund, and Janet Flanner. Monnier was, in the self-assured title she chose for her advertisements, Directrice of her French-language bookstore, La Maison des Amis des Livres. To the writers who gathered there, including Paul Valéry, André Gide, James Joyce, and Valery Larbaud, Monnier’s bookstore on the Left Bank was the heart of literary Paris. Without her example, Beach’s Shakespeare and Company would never have existed. Monnier taught her how to run a business, how to deal with French bureaucracy, how to manage cantankerous people. Beach never made an important decision without first consulting her.

Monnier’s emergence as a force in French letters was in some ways as remarkable as Rimbaud’s four decades earlier. She had no connections, no serious university credentials—only a mother who encouraged her to read and a father who entrusted her with a small settlement won after an accident, which was just enough capital to start her business in 1916. Three years later, Sylvia turned up on Adrienne’s doorstep in quest of an education in modern French verse:

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )

One day at the Bibliothèque Nationale, I noticed that one of the reviews—Paul Fort’sVers et Prose, I think it was—could be purchased at A. Monnier’s bookshop, 7 rue de l’Odéon, Paris VI. I had not heard the name before, nor was the Odéon quarter familiar to me, but suddenly something drew me irresistibly to the spot where such important things in my life were to happen.

>How far down from ‘up’ we’ve come

>

Ryan Sayre on the lost dreams of verticality @ 3Quarks Daily.

Elisha Otis was a solver of problems—practical problems involving bread ovens, steam engines, bed frames, and the like. Faced with the problem of safely bringing debris down from the second floor of his workshop, in 1852 he repurposed a railroad brake into an emergency elevator brake that would stop the lift cold in its tracks should the supporting cables snap. This small innovation opened an entirely new kind of space; a space we might call the ‘up’. ‘Up’ had of course always existed, but never before as a habitable territory. As a place for work, life, and leisure, ‘up’ would have to be imagined. While colonial powers in the early 20th century were busy stretching railroad lines across continents, urban engineers in cities like Chicago and New York were beginning to bend Otis’ elevator tracks ever further upward into uncharted verticality.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )For a short three to four year period in the late 1920s and early 1930s, New York City drove its skyline 70, 87, and then 102 stories into the air. The expedition marked a transformational moment in the city. During these few years city traffic was detoured skyward. The city’s profile was nearly flipped on its axis. The goal of city planners was to rationalize the city and the ‘up’ seemed like the most efficient direction to take a growing population. But rationalization and efficiency are never linear; the stories of buildings are marked by countless twists and turns.

>Our history is no longer ours

>

Jason Farago reflects on the opera “Nixon in China” and the promises of the past @ n+1.

At the opera last week, first two boxes down from mine, then right in front of me at the bar, was the former governor general of Canada. As celebrity sightings go it doesn’t beat sitting next to Dr. Ruth once, but a head of state is a head of state. That was not what C. thought, though. “Do you know who that is?” I asked, and he did not miss a beat: “Unless she’s a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, I’m not interested.”

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )Who could blame him? Who else matters? Much has been made lately of the transformed position of Tricky Dick in the American imagination, but what was really inconceivable for John Adams and his collaborators when they wrote Nixon in Chinain 1987 was that, by its Met premiere in 2011, the presidency itself would be approaching global irrelevance. It’s a funny, Egyptian-inflected moment, of course. And it’s perhaps unfair to consider the US (or the President specifically) only in apposition to the People’s Republic—though the Chinese setting of the opera seems almost overkill, as any work of art about America today would be about China by default. But as Nixon sings in Act I, while China lives in the present, in America “it’s yesterday night.” Perhaps the day is not far off when Barack Obama in Box 15 will excite C. just as little.

>Undeceive ourselves

>

|

| Raphaelle Peale @ Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art/ |

Wendy Bellion reflects on the pleasures of trompe l’oeil and the links between citizenship and deception in early US history @ Common Place.

I have a confession to make.

In the course of writing my book on art and illusion in the early republic, I was taken in by a trompe l’oeil object.

It was October 2002. I had completed my doctoral dissertation the previous year and was just beginning the work of revising it for publication. In the meantime, I had contributed a number of entries to an exhibition catalogue for a large show about trompe l’oeil that was being organized by the National Gallery of Art, Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting. At the exhibition’s opening, I was thrilled to see many of the pictures I had studied, pondered, and written about. Cleverly positioned near a museum staircase was Charles Willson Peale’s trompe l’oeil Staircase Group (1795), a double portrait of Peale’s sons Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay that reportedly fooled no less a figure than George Washington back in the day. In another room I encountered the marine artist Thomas Birch, leaning out from the space of his portrait to rest his arm on the picture frame. Elsewhere was Raphaelle Peale’s masterful Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception (c. 1822), which appeared to conceal a picture of a female nude behind a cloth. According to family lore, Raphaelle’s wife—presumably peeved by her husband’s naughty imagination—took a swipe at the painting in an attempt to remove the cloth.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )

I knew all the tricks of trompe l’oeil walking into this exhibition. I knew the stories of spectators deceived by wily pictures, of birds that pecked at painted grapes and dogs that climbed the step of the Staircase Group. I knew better than to get taken in by an illusion. And then my vanity got the better of me.

>The Fame Machine

>

John Tresch considers the technologies of fame from Gilgamesh to Facebook @ Lapham’s Quarterly.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( None so far )“The Fame Machine,” a brief satire included in French author Auguste de Villiers de L’Isle-Adam’s collection of 1883, Cruel Tales, asks in precise, concrete terms just what celebrity is. Fame—or “la gloire” in the original, which means glory and renown, as well as the halo surrounding an image of Christ’s head—is a vague and vaporous notion, a sort of smoke that emanates from truly sublime works and individuals. The narrator of Villiers’ tale offers the steam engine as proof that elusive and vaporous phenomena can be put to work with very palpable effects. Thus even theatrical success can be reduced to its material components—applause, cheers, stamping feet, sighs, gasps, and well-timed devotional bouquets, as well as the barely stifled guffaw sparking the eruption of laughter and the “wow-ow,” the resonating cascade of bravos launched in close succession.

Although the claque, or paid troop of applauders, is an unshakable institution in the nineteenth-century Parisian theater, its work, paid for by the performance, is too unpredictable and piecemeal for an age that demands certainty and uniform efficiency.The hero of the tale, engineer Bathybius Bottom, is an inventor and true devotee of the arts, willing to transform, for a price, any theater into a fame machine. No longer will the success of a play be left to chance or to the incompetence of a hired stooge who might miss his cues, laughing at a tragic turn or cheering the villain. At the flipping of a switch, artificial hands flutter gratifyingly together; the legs of the seats lift and strike the ground in exact imitation of appreciative canes and walking sticks; the cherubim adorning the loges and the proscenium reveal themselves to be no mere ornament but rather lung-sized bellows calling out their approval of the author and the actors, confirming the artwork’s sanctification. The machine also can be directed to plant favorable reviews in the press, and if for some reason a negative response is demanded, it will hiss, boo, and make catcalls. Controlled by an operator who must be above any personal interest, Dr. Bottom’s invention transforms the entire theater into a machine for producing glory: a material apparatus that brings about spiritual effects.

>An accumulation of details that results in History

>

Kim Dana Kupperman on the power of small love letters @ Brevity.

The real history of the world happens in small ways because it concerns the history of love, itself a series of small events. A glance might shift the order of everything, move the heart into open terrain. A heartbeat might slow the unfolding of a wing, which may in turn cause a brief lull in the tide. A boat might then be delayed. That series of small hesitations might change history. I like to think of this quantum condition as a matter of small love letters.

Read Full Post | Make a Comment ( 1 so far )The glance. The altered heart. The wing in a backwards origami. The slowing of the tide that delays an arrival or a departure. An accumulation of details that results in History.